Authored by Randy DeSoto via Western Journal

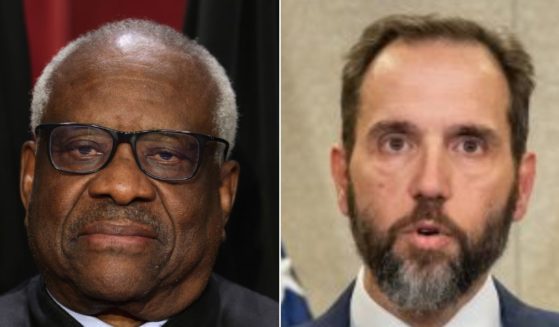

In a concurring opinion to Monday’s U.S. Supreme Court presidential immunity ruling, Justice Clarence Thomas argued that Jack Smith’s appointment as special counsel is unconstitutional.

Chief Justice John Roberts wrote in the majority opinion that the president “is entitled to at least presumptive immunity from prosecution for all his official acts.”

This is a much broader scope of immunity than Smith’s prosecutors have argued before the Washington, D.C. federal district court, where former President Donald Trump’s 2020 election interference case is being conducted.

Thomas, along with justices Samuel Alito, Neil Gorsuch and Brett Kavanaugh, signed on to the majority opinion, while Justice Amy Coney Barrett joined in most of it.

Justices Sonia Sotomayor, Elena Kagan, and Ketanji Brown Jackson all dissented.

The case has been sent back to the federal district court to determine which wrongdoing, if any, contained in Smith’s 45-page indictment against Trump falls within what could be deemed his official acts as president.

In his concurring opinion, Thomas explained, “I write separately to highlight another way in which this prosecution may violate our constitutional structure. In this case, the Attorney General purported to appoint a private citizen as Special Counsel to prosecute a former President on behalf of the United States. But, I am not sure that any office for the Special Counsel has been ‘established by Law,’ as the Constitution requires.”

Should Jack Smith be removed as special counsel?

“If there is no law establishing the office that the Special Counsel occupies, then he cannot proceed with this prosecution. A private citizen cannot criminally prosecute anyone, let alone a former President,” the justice added.

Before he was appointed special counsel by Attorney General Merrick Garland in November 2022, Smith served as the chief prosecutor for the special court in The Hague in the Netherlands. Before that, he was a prosecutor in the U.S. Justice Department, according to a DOJ news release.

“If this unprecedented prosecution is to proceed, it must be conducted by someone duly authorized to do so by the American people,” Thomas argued.

The justice then went into some history, highlighting, “The Founders broke from the monarchial model by giving the President the power to fill offices (with the Senate’s approval), but not the power to create offices.”

This requirement was an intentional check on executive power.

“If Congress has not reached a consensus that a particular office should exist, the Executive lacks the power to create and fill an office of his own accord,” Thomas wrote.

“It is difficult to see how the Special Counsel has an office ‘established by Law,’ as required by the Constitution. When the Attorney General appointed the Special Counsel, he did not identify any statute that clearly creates such an office,” he added.

Fox News reported that the issues Thomas raised in his concurring opinion mirror some of the points made by former Reagan Attorney General Edwin Meese in an amicus brief to the Supreme Court in Trump’s presidential immunity case.

He argued that “even if one overlooks the absence of statutory authority for the position, there is no statute specifically authorizing the Attorney General, rather than the President by and with the advice and consent of the Senate, to appoint such a Special Counsel.”

Meese said the only way Garland or any other attorney general can designate a special counsel is by assigning an existing U.S. attorney (all of whom must go through Senate confirmation) to oversee the criminal prosecution.

Trump’s attorneys have raised the issue of the constitutionality of Smith’s appointment in the classified documents handling case being brought in Florida and overseen by federal district court Judge Aileen Cannon.

The New York Times reported, “Mr. Smith’s deputies have countered that under the appointments clause of the Constitution, agency heads like Mr. Garland are authorized to name ‘inferior officers’ like special counsels to act as their subordinates.”

But in his concurrence, Thomas questioned this reasoning, writing that the only way Smith would be an “inferior officer” is if “a statute created the special counsel’s office and gave the attorney general the power to fill it.”